Year in review: 2019

As is now a bit of a tradition on these pages, I’m again compiling a review of last year’s main birding events. Senegal’s bird year 2019 was a pretty good one, with the usual decent mix of new discoveries, rare vagrants, scarce migrants, range extensions and new breeding records.

First things first: last year saw the addition of two new species to the country’s avifauna, so rather similar to previous years – on average, there have been two additions per year during 2014-2018. First a Willcock’s Honeyguide in Dindefelo nature reserve found by Nik Borrow and his group in January, then the discovery of a small group of Cuckoo Finches at Kagnout in Casamance, in February by Bruno Bargain, Gabriel Caucal and Adrien de Montaudouin. As predicted back in 2018, both Dindefelo and Casamance are obviously key areas for finding new birds in the country. Both species are known to occur in neighbouring countries so these additions are not too much of a surprise, and will likely show up again in Senegal in coming years. These “firsts” bring the total number of species confirmed to occur in Senegal to 674, with seven additional species listed as requiring confirmation. The full checklist as per IOC taxonomy (v.8.1) may be found here.

Next up, the usual lot of vagrants: from North America, the now annual American Golden Plovers (Palmarin in April, and Yene in December), the country’s fourth Pectoral Sandpiper at Lac Mbeubeusse on 5.10, and a Lesser Yellowlegs wintering at Technopole – apparently the longest stay recorded in Africa (at least 71 days!), and most likely the same bird seen several years in a row now. Two Laughing Gulls that were present at Technopole in April-May – an adult in breeding plumage and a first-summer bird – were the 6th and 7th records; the immature was also seen at Ngor on 22.5. Also at Technopole were at least two different Franklin’s Gulls, one in January and two in April-May including an adult displaying to other gulls. A Lesser Jacana was found by Vieux Ngom on 16.3 on the Lampsar, while a Spotted Creeper on 17.12 at Kamobeul (Ziguinchor) was another rarely recorded Afro-tropical vagrant. And finally from Europe, a Little Gull – possibly not a true vagrant but rather a very scarce winter visitor – was seen on 8.3 at Ngor, and a European Golden Plover was at Saloulou island (Casamance) on 25.2.

Scarce migrants included a few species of ducks that are rarely reported from Senegal, starting with these three Gadwalls found by Simon Cavaillès at Technopole in January, which were probably the same birds as those seen in December 2018 in The Gambia. A Eurasian Wigeon was present at the same time; while the latter is regular in the Djoudj, both ducks were apparently seen for the first time in the Dakar region.

Almost a year later this pair of Ferruginous Ducks on a small dam at Pointe Sarène near Mbour on 24.12 were a real surprise in this location. Apparently they didn’t stick around: earlier today (19.1.20) I had the chance to visit the dam again but no sign of our two Palearctic ducks…

An African Crake found by Miguel Lecoq in a dry river bed at Popenguine NR on 12.7 was highly unusual. The two Short-eared Owls at Technopole in January (with one still here on 11.2) were possibly returning birds from the 2017-18 influx as they roosted in exactly the same location; another bird was found in the Djoudj on 26.12 by Vieux and Frank Rheindt. Perhaps more unexpected was a Marsh Owl that was actively migrating at Ngor on 8.10, coming from the north out at sea, but even more spectacular was the discovery of an Egyptian Nightjar by Frédéric Bacuez on his local patch at Trois-Marigots, on 23.10 (an early date and first in this location); in the Djoudj NP, a somewhat classic location for the species, three birds were seen several times from 23.11 up to mid December at least.

A few Red-footed Boobies were again seen at Ngor: an adult on 3.7 and likely the same bird again on 22.7, then daily from 9-12.8 (with two here on 17.8), and again an imm. seen twice in November. These are the 5th to 7th records, a remarkable presence given that the first record was in October 2016 only! As usual, several Brown Boobies were seen as well but we didn’t get the chance to properly check on the birds at Iles de la Madeleine this past year. Other scarce seabirds seen from Ngor were a Balearic Shearwater (18.11), a Bulwer’s Petrel (5.12), several Leach’s Storm-Petrels (11 & 13.11), and some 30 Barolo’s/Boyd’s Shearwaters that passed through in August and September. A Baltic Gull (fuscus Lesser Black-backed Gull) at Technopole 27.1 was our first record here.

Quite a few birds were reported for the first time from Casamance by Bruno and friends, and several resident forest species that had not been seen in many years were “rediscovered” this past year, such as Black-shouldered Nightjar, Black Sparrowhawk, White-throated and Slender-billed Greenbuls, Flappet Lark, Red-faced and Dorst’s Cisticolas – the online Casamance atlast can be found here. Several Senegal Lapwings were again seen towards the end of the rains, and a Forbes’s Plover at Kagnout on 17.2 was definitely a good record as the species had previously been reported only on a few occasions from the Niokolo-Koba NP.

A Brown-throated (= Plain) Martin feeding over the lagoon at Technopole on 28.4 was a first for Dakar; this species is rarely seen in Senegal it seems. A few Moltoni’s Warblers were reported in autumn including at least one on 20.10 at Mboro, where Miguel also noted several northward range extensions such as Fine-spotted Woodpecker, Grey Kestrel, Splendid Sunbird, and Orange-cheeked Waxbill. The observation of two Mottled Spinetails some 15km south of Potou (Louga region) is the northernmost so far and seems to confirm the presence in this part of the country, following one in the same region in January 2018. A pair of Little Grey Woodpeckers at Lompoul and the discovery of Cricket Warbler in the Gossas area (Diourbel) are also noteworthy as they are just outside known distribution ranges for these two Sahelian species. More significant is the observation of a Long-billed Pipit on the Dande plateau near Dindefelo on 9.2, as this is the first record away from the Djoudj area, raising the possibility that the species is breeding in the vicinity.

Additional good records for the Dakar region included a White-throated Bee-eater on 12.8, a Red-breasted Swallow near Diamniadio on 11.10 and Grasshopper Warblers at Yene lagoon on 8 & 15.12, as well as at Lac Tanma (Thiès region) on 27.10 – and more surprisingly, one was found aboard a sail boat some “400 Miles South West Of Dakar” on 13.9. Last year we documented oversummering of Yellow-legged and Mediterranean Gulls on the peninsula.

We also continued our modest efforts to survey breeding Black-winged Stilts at several sites in Dakar, Ziguinchor and Saint-Louis; the findings of these should be formally published later this year. The Horus Swift colony was visited on several occasions (Jan.-March and Nov.-Dec.) with further evidence of breeding. A pair of Tawny Eagles at their nest site on a high tension pylon near Ndioum, where they are known since at least 2015, were seen again in December by Frédéric and Jérémy. Yellow-throated Longclaw was found to be breeding at lac Mbeubeusse and probably at lac Rose as well: more on the species in this post.

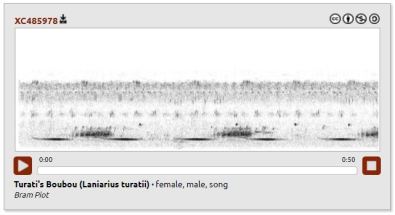

In July we found several additional pairs of Turati’s Boubou right on the border with Guinea-Bissau, a bit further to the south of the site where Bruno initially found the species, in October 2018 near Ziguinchor. Also in Casamance, breeding was confirmed for Common Buttonquail, Golden-tailed Woodpecker, and a whole range of other species.

Another noteworthy record is that of a group of 113 Eurasian Griffons in the Djoudj NP on 2.11 – apparently the largest flock ever recorded in Senegal! This surely reflects the general increase in numbers of what used to be a rather scarce species it seems – read up more on the status of this vulture in Senegal in this post on Ornithondar.

As usual, a few interesting ring recoveries were obtained, including several returning birds, providing further evidence for site fidelity and local movements between key sites for e.g. Black-tailed Godwits and Ospreys of course, but also for a Eurasian Spoonbill from Spain – more on this in a future post. A Gull-billed Tern from the Neufelderkoog colony in northern Germany was also a good recovery, just like the many Sandwich Terns that we managed to read at Technopole in April-May with birds originating from Ireland, the UK, the Netherlands and Italy! Also of note were a French Black-headed Gull, the first colour-ringed Greenshank and wing-tagged Marsh Harrier in our ever-growing database, and last but not least the first recovery of a Croatian-ringed bird in Senegal, an Audouin’s Gull seen at three sites in Dakar in January and February.

During 2019 I was fortunate to continue our regular coverage of Technopole but also for the third consecutive year of seabird migration at Ngor, and managed a few trips further afield: the northern Saloum delta (Simal, Palmarin), three trips to Casamance (January, May, July), the Petite Côte (at long last explored the lagoons at Mbodiene!), the Langue de Barbarie and Trois-Marigots in April, the Djoudj and other parts of the lower Senegal valley (November), and finally Toubacouta in December. Oh and a memorable day trip on a successful quest for the enigmatic Quail-Plover!

Other blog posts this past year covered the status and distribution (and a bit of identification!) of Seebohm’s Wheatear, Iberian Chiffchaff, and Western Square-tailed Drongo.

Another series focused on recent ornithological publications relevant for Senegal, in three parts. I’m not sure how I managed but in the end I was involved in quite a few articles published in 2019: the autumn migration of seabirds at Ngor and the status of Iberian Chiffchaff in West Africa (the latter with Paul Isenmann and Stuart Sharp) in Alauda, the first records of Eurasian Collared Dove and of Turati’s Boubou in Senegal (the latter with Bruno Bargain) published in Malimbus, and finally two papers in the Bulletin of the African Bird Club: a short piece on the hybrid shrike from lac Tanma in 2017 (with Gabriel Caucanas), and a review of the status of the Short-eared Owl in West Africa, following the influx during winter 2017/18.

Many thanks to all visiting and (semi-)resident birders who shared their observations through eBird or other channels, particularly Miguel, Frédéric and Bruno. The above review is of course incomplete and probably a bit biased towards the Dakar region: any additions are more than welcome and will be incorporated!

The Tigers of Toubacouta

Our main target during a brief visit to the Saloum delta national park, just last week, was a rather unique bird that had so far eluded us: the enigmatic Tigriornis leucolopha. Its presence in the area has been known for a few years only, but it quickly became a classic target species for visiting birders – particularly those touring the country with the excellent Abdou “Carlos” Lo who is based at Toubacouta. But it’s one of those birds that requires a bit of planning combined with a decent dose of luck. It’s certainly not enough to just get on a pirogue into the mangrove forest where it lives: thanks to Abdou’s expert advice, we made sure to set off at low tide even if this meant going out in the mid-afternoon heat.

I’d always thought that the White-crested Tiger Heron (Onoré à huppe blanche) was more of a nocturnal or at best a crepuscular species, but that’s obviously not the case: when the tide is low, it will come out to the edge of the mangrove to fish, apparently at pretty much any time of the day. We were extremely lucky to actually witness this first-hand: after an unsuccessful attempt in one of the bolongs near the island of Sipo, our piroguier Abdoulaye eventually spotted a Tiger Heron, very much out in the open as we drifted past at fairly close range. It quickly entered the dense mangrove forest only to re-appear in a more concealed area a few meters away, carefully navigating the labyrinth of roots and tangles.

White-crested Tiger Heron / Onoré à huppe blanche, Sipo, 25.12.19 . Check out its amazing yellow-and-burgundy eye

As we were watching and photographing this dream bird, it caught a small fish, gobbled it down and quickly vanished back into the forest.

Note the rather cold colours and overall rather pale plumage of this individual, something that’s also visible in other pictures from the Saloum: possibly an adaptation to the mangrove environment here? Compare with the darker and more rufous birds found in e.g. Ghana and Gabon, for instance in the photo gallery of the Internet Bird Collection.

All in all, quite a surreal moment and a perfect Christmas present – Frédéric and I were of course hopeful we’d get a glimpse of this secretive heron, but certainly never thought we’d get such amazing views. It easily ranks in my Top 10 of Best African Birds Seen So Far, alongside the likes of Quail-Plover, Egyptian Plover, Crab Plover, Pel’s Fishing-Owl, Pennant-winged Nightjar, Böhm’s Spinetail, Little Brown Bustard, Wattled Crane and of course the most bizarre Grey-necked Picathartes (and Shoebill and Locustfinch and Spotted Creeper and… so on). Just like some of these species, the White-crested Tiger Heron – or White-crested Bittern as it is sometimes called – is the unique representative of its genus.

Here’s one more picture of this amazing bird, taken by Frédéric as we first spotted it – pretty cool, right?

White-crested Tiger Heron / Onoré à huppe blanche (Frédéric Bacuez/Ornithondar)

Earlier that same day – much earlier actually, about 6.45 am to be precise! – we had already heard the rather ghost-like song that’s typical of the species, right from the small jetty at our campement villageois at Dassilame Serere. The song is not dissimilar to the Eurasian Bittern, a monotonous booming “whooooooom” uttered at a very low frequency, at 4-6 second intervals, which however got easily drowned in the dawn chorus of roosters, donkeys, dogs and goats of Dassilame… and which stopped abruptly just as daylight started to take over the night. The next morning I was better prepared and actually managed a few mediocre recordings when two distant birds were singing to each other deep in the mangrove, again pre-dawn and stopping before it properly got light. These turned out to be the first to be uploaded onto xeno-canto: check out the species page here (and make sure to turn up the volume to the max as the sound is quite subdued).

Tiger Bird habitat:

White-crested Tiger Heron / Onoré à huppe blanche (yes it’s in the picture… just impossible to see, even when you know where it is! When we first saw it, it was out on the tiny patch of mud to the right)

The Tiger Heron was initially thought to be restricted, in Senegal that is, to the Basse-Casamance region, where the first record is that of two nestlings collected and raised near the village of Mlomp (Oussouye) in 1979, followed by a few sightings in 1980-81 in the Parc National de Basse-Casamance and a nest found in Nov. 1980 north of Oussouye (A. Salla in Morel & Morel 1990); as far as we know, the next confirmed record was obtained in… 2017, at Egueye island, also near Oussouye, on January 1st, so almost 36 years later.

The first mention of the species in the Saloum delta is from 1980 by A. R. Dupuy (1981), while the next published record is from 2004 only – see comment by John Rose on this blog post [updated 4 Jan 2020] and the short paper by Rose et al. (2016). The next observation that I could find is from January 2007, of a bird photographed near Missirah by Stéphane Bocca. The fact that we heard two birds singing from Dassilame Serere, the records near Toubacouta and Sipo as well as the observation from Missirah all suggest that the Tigriornis is fairly well established here, and may well be widespread throughout the vast mangroves of the Saloum delta: targeted searches are likely to turn up more birds in other parts of the delta. The species is also present in mangroves along the Gambia river, where first discovered in 1996 (Kirtland & Rogers 1997). Casamance and especially the Saloum delta are actually right on the edge of the distribution range of the species, which extends from central Africa through the Congo-Guinean forest zone. In Senegal and Gambia, it primarily inhabits the vast mangrove forests, though it may also still occur in the swamp forest of the Basse-Casamance NP, i.e. in similar habitat to that occupied further south such as in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana.

Other good birds seen during our boat trip included several majestic Goliath Herons, Palm-nut Vultures, a colour-ringed German Osprey (more on this later), a few Blue-breasted Kingfishers and Common Wattle-eyes (both heard only), as well as an unexpected Swamp Mongoose seen in full daylight (Héron goliath, Palmiste africain, Balbuzard, Martin-chasseur à poitrine bleue, Pririt à collier, Mangouste des marais).

During our stay in the Toubacouta area, we also visited the Sangako community forest, Sandicoly, and bush/farmland near Nema Ba: plenty of birds everywhere, though no real surprises here, except maybe for a fine pair of Bateleurs, a species that’s right on the edge of its regular range here. Other goodies for us northerners included Swallow-tailed Bee-eater, Grey-headed Bushshrike, White Helmetshrike, Bruce’s Green Pigeon, Four-banded Sandgrouse and many more of course (Guêpier à queue d’aronde, Gladiateur de Blanchot, Bagadais casqué, Colombar waalia, Ganga quadribande). Also a nice series of owls heard from our campsite: Greyish Eagle Owl, African Scops Owl, Pearl-spotted Owlet and Barn Owl! (Grand-duc du Sahel, Petit-duc africain, Chevêchette perlée, Effraie des clochers).

Swallow-tailed Bee-eater / Guêpier à queue d’aronde

With the addition of the Tiger Heron but also Ferruginous Duck (a pair on a small dam near Mbodiene, 24.12; Fuligule nyroca), my Senegal list now stands at 530 species: which one will be next?

Yellow-throated Longclaw in Dakar – irregular visitor or an overlooked resident?

There’s a handful of bird species here in Dakar that remain rather enigmatic, and whose status and patterns of occurrence remain to be fully understood. One of these is the Yellow-throated Longclaw (Macronyx croceus), a member of the pipits and wagtails. Longclaws are a genus that is entirely restricted to Africa where eight different species are known, some of which have small or patchy distribution ranges. The Yellow-throated Longclaw is certainly the most widespread species, but here in Senegal we’re right at the edge of its range: while nowhere common, it’s probably quite widespread in Basse-Casamance (Ziguinchor, Oussouye, Cap Skirring/Diembering, Kafountine/Abene… even Sedhiou a bit further inland). There are just a handful of observations from north of the Gambia, where the species is apparently on the decline, at least in coastal areas where very few recent sightings it seems. The scant information that we have is mostly based on old records from the Dakar peninsula, more on these later. It’s clear though that this is a very little known species that at best is obviously scarce and localised, and while I certainly have it somewhere in the back of my mind when visiting lac Rose, I didn’t think I’d ever see it here.

Until yesterday morning, when I came across not one but two of these cool “sentinels” as they’re called in French: first one on the margins of the Mbeubeusse wetlands (99% dry now!), a bird flying over a reedbed and landing out of sight quite a distance away. A rather frustrating sighting but just decent enough to confirm the id: broad wings, medium-long tail with white corners, vivid yellow throat and breast with black markings on side of throat. I may have heard it singing shortly before I saw it but not sure as it called only once and Crested Larks can sound a bit similar!

The second bird was found barely an hour later at lac Rose, right at the Bonaba Café on the northern shores of the lake, and “performed” much better than the first! Upon arriving at this site, I could clearly hear it singing for several minutes on end; it even allowed me to get quite close so I could document this bird on camera (and on sound recorder: a sample of its simple yet rather melodious one-note song here.

These are the old records known from the Dakar area:

- August 1968 – “seen several times in coastal region 20 km east of Dakar” (M.P. Doutre; Morel & Morel) – this may well be near lac Malika or Mbeubeusse

- 9 April 1977 – 2 singing, Lac Rose (W. Nezadal on eBird)

- January 1984 – “Dakar” (Paul Géroudet in M&M)

- February 1990 – one seen “north of Dakar” within the Dakar atlas square, but this could be anywhere between Guediawaye and Kayar… (Sauvage & Rodwell 1998)

- 17 February 1991 – 1, Lac Malika (O. Benoist on eBird)

More recently, there’s an observation of no less than five birds on 18 Jan. 2011 at lac Rose seen during a tour organised by Richard Ottvall for the Swedish AviFauna group. Almost five years later, another mention from the same site, unfortunately without any further comments other than that it was on 20 November 2014 at lac Rose (near the southern edge, not far from Le Calao lodge), by J. Nicolau during a scouting visit for Birding Ecotours. The only other recent record north of the Gambia that I came across was of two birds in the Saloum delta (though where precisely?) on 8 January 2017 (J. Wehrmann on observation.org).

Could it be that there are just a few birds that are mostly escaping us – some relictual population from greener days when rains were plentiful here? It’s hard to believe though that if they were present year-round, that we haven’t come across them since we do visit Lac Rose and Mbeubeusse fairly regularly, in all seasons. Or are they present only certain years, and if so at what time of the year? The series of observations from the late sixties up to early nineties is certainly intriguing and would suggest that the species was fairly well established in the Niayes region, especially when one factors in the even lower observer pressure than currently. With records from January (2), February (2), April (1), June (the two in this report), August (1) and November (1) it seems that they can be expected pretty much at any time of the year. More investigations are needed of course and we’ll see if we can find out more in coming months.

Some other good birds from the weekend…

Also on the lake shore were a few Lesser Black-backed Gulls with a second summer Yellow-legged Gull in the mix, some 33 Audouin’s Gulls (i.e. far less than last year at the end of June), Little Terns at colony, a female Greater Painted Snipe (first time I see this species here) and a few other waders (nine Sanderling, 40+ Common Ringed Plovers. a few Greenshanks and Grey Plovers, one Redshank), as well as at least three Brown Babblers – my first in the Dakar region I believe (Goélands brun, leucophée, d’Audouin; Sternes naines, Rhynchée peinte, Sanderling, Grand Gravelot, Chevaliers aboyeur, Pluvier argenté, Gambette, Cratérope brun).

A brief walk and a quick scan of the steppe to the north-east revealed a few Singing Bush Larks and the usual loose flocks of Kittlitz’s Plovers (31 birds including at least 2 small chicks and an older juv.), though no Temminck’s Coursers were seen this time round. Also here was another Osprey and a few Blue-cheeked Bee-eaters, which were also heard around the lake (Alouette chanteuse, Gravelot pâtre, Balbuzard pêcheur, Guêpier de Perse).

At Mbeubeusse, apart from the Longclaw the surprise du jour was a fly-over pair of Spur-winged Geese (Oie-armée de Gambie), no doubt looking for fresh water…

Target of the day however was Black-winged Stilt – well, in addition to a few others such as the gull flock I wanted to check on – as I was keen on gathering more breeding data. More on this in a later post, but here’s already a picture of an adult with one of its chicks, from Mbeubeusse where there’s hardly any water left in the small pond close to the main road (= near the end of the Extension VDN). Just like last year, several families and nests were found at Lac Rose, and this morning at Technopole I managed to do a fairly extensive count of the number of families and nests. The breeding season is still in full swing and I hope that many of the birds that are still incubating will see their eggs hatch: with low water levels, predation by feral dogs, Pied Crows, Sacred Ibises etc. may be even more of a risk than usual. Overall it certainly seems that there are fewer nests and fewer grown chicks than last year – again, more on this later!

Not a target but always a pleasure to watch these highly underrated doves:

Other stuff of interest from this morning’s visit to Technopole – shortly after the first rain of the season (a very small shower only, but nevertheless: first rain since early October!) – were four Broad-billed Rollers which just like last year seem to favour the area to the NW of the main lake, again Diederik Cuckoo singing, the same Yellow-legged Gull as the previous day at Lac Rose, close to 1,500 Slender-billed Gulls including the first juveniles of the year, as well as the first Black-tailed Godwits of the “autumn”: these are birds that have just arrived back from western Europe, most likely failed breeders. (Rolle violet, Coucou didric, Goélands leucophée et railleur, Barge à queue noire)

Full list here.

Red-necked Falcon / Faucon chiquera

Note!

Visitors to Technopole should know that there is now a poste de contrôle (check point) near the entrance, just after the Sonatel building, manned by rangers from the DPN (National Park Service). This is the first tangible sign that the newly acquired protected status of the site is actually making a difference; hopefully their presence will help prevent illegal dumping and may give potential visitors more of a sense of security. Please do stop and explain that you’re there to watch birds (they will ask anyway, and if you don’t stop they’ll tell you off on the way out). Do note that entrance remains free to all, and that there’s no entrance fee.